They Only Connect

Los Angeles Times

November 25, 2001

By Robert Hilburn

Staind is a standout in dark rock not for its song craft, but for a straightforward style that speaks directly to fans.

|

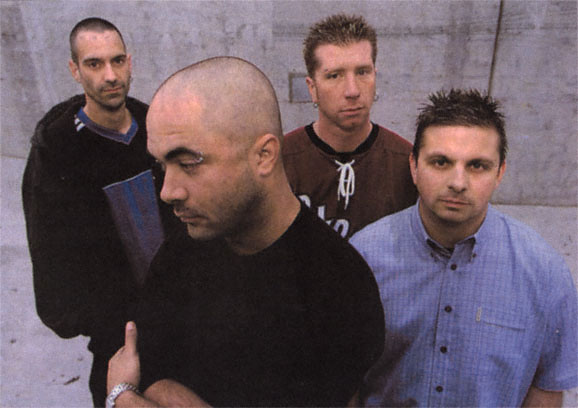

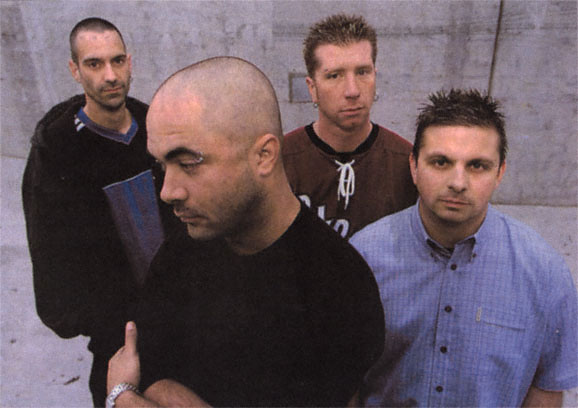

It's easy to dismiss it as a hollow ritual these days when young rock fans hold up cigarette lighters during a concert. But jaded rock veterans should realize that young fans today may be motivated by the same genuineness that first inspired someone, maybe around the Woodstock era, to raise a flame during a ballad as an expression of affection and bonding. Especially if those fans are at a Staind concert. Staind is a quartet from Massachusetts that has worked its way up through the same aggressive, usually relentlessly dark metal, rap-rock and hard-rock world that gave us Korn, Limp Bizkit and many other contemporary best-sellers. The group was even discovered by Limp Bizkit's Fred Durst. But Staind's highly melodic style and frequently vulnerable themes would fit more comfortably into the post-grunge world of Pearl Jam. Wherever you place it, Staind is hot. Its latest album, "Break the Cycle," has sold more than 3.5 million copies since May. Singer Aaron Lewis, whose voice impressed Bono enough for the U2 leader to bring him aboard for the recent "What's Going On" charity recording, writes about many of the same subjects on every other hard-rock or metal album of recent years: alienation and lack of self-esteem. But he brings them a perspective and balance that are usually missing. The ballad "It's Been Awhile" was No. 1 on the modern rock and mainstream rock radio playlists for almost four months this year—as revolutionary a showing in its way as Ice Cube's tender "It Was a Good Day" and Tupac Shakur's sweet "Dear Mama" were in the macho hard-core rap world of the early '90s. In the song, Lewis lists many of the dark moments in his life: "It's been awhile since I could hold my head high ... It's been awhile since I could say I wasn't addicted ... It's been awhile since I've seen the way the candle lights your face." The song is invariably dismissed by adults when I play it for them as more of the whining that has turned them off to modern rock since the arrival of Nirvana and Pearl Jam. But they are missing the point of the song (just as other adults missed the point a decade ago of many Nirvana and Pearl Jam songs). The message of "It's Been Awhile" is that it is possible to move beyond the issues of low self-esteem that sometimes seem crippling to young people. The song's narrator has reached a point where he has begun to see life in more positive terms and accept responsibility for some of his past mistakes. In the song's closing line, he even says he's sorry to those he has hurt or let down. In "Outside," another song that inspired hundreds of fans to hold up lighters during Staind's set during the Family Values Tour stop at the Arrowhead Pond this month, Lewis looks past the alienation and despair that have turned '90s metal/rock into a caricature. He tries to comfort a troubled friend by saying he can see through the ugliness both feel inside and can imagine better days ahead. Although Rolling Stone put Staind on its cover, rock critics generally have been as slow as parents to notice that Staind may be helping rock turn a page by showing that the young audience is ready to emerge from its decade of darkness. The band, whose instrumental textures range from slashing to graceful, consists of Lewis, guitarist Mike Mushok, drummer Jon Wysocki and bassist Johnny April. One reason Staind is easy to overlook is that its music isn't artful in the way that meets the usual critical standards. For starters, the songs are so straightforward they don't fit into any revered style. Lewis writes the words in an almost stream-of-consciousness style when the musical tracks, written by the entire band, are finished. There is little subsequent editing. The results aren't complex or poetic enough to be Dylanesque, nor abstract and provocative enough to be Cobain-like. All they do is connect. In "Epiphany," one of Staind's most evocative songs, Lewis even makes fun of his inarticulateness. "I speak to you in riddles because my words get in the way." Backstage at the Pond, Lewis is as straightforward as his music. He was shocked, he says, by the acceptance of "Break the Cycle" because he knew it went against the commercial grain in rock's dark Kornfield. In his songs, Lewis simply tells his story. "It's all autobiographical ... the good times and the bad," he says backstage. It was mostly bad times in the group's first two albums, the self-financed 1996 debut, "Tormented," and the breakthrough 1999 Elektra/Flip collection, "Dysfunction," which sold more than 1 million copies. At 29, Lewis is a good 10 years older than the average Staind fan, and he wondered before releasing "Break the Cycle" whether the audience would relate to its transition from the youthful despair of the first two albums—he once had fleeting thoughts of suicide—to his more hopeful outlook. "In the first album, I'm a mess," he says, flicking ashes from one of his ever-present cigarettes. "It's like salt in open wounds. In the second album, things are starting to become a little bit clear. I'm starting to see that I'm in a mess and trying to figure out what to do about it. This record breaks the cycle. It's finally seeing the light at the end of the tunnel. "I didn't know if the audience that responded to 'Dysfunctional' would even begin to understand where we went in 'Break the Cycle,' but it was the only thing we knew how to do. I have to be honest with myself to make it work when it comes to music—and that means it's always going to be a bit of a question in terms of what is going to come out in our music. I'm not sure I have a choice in it." Anger has been a liberating force in rock—and parents have long been a target for that anger. It started out as mostly playful grumbling in such early rock and R&B hits as Eddie Cochran's "Summertime Blues" and the Coasters' "Yakety Yak." By 1967, however, the Doors' Jim Morrison was fantasizing in "The End" about killing his father. But even some of those original Doors fans were taken aback 25 years later when, as parents, they felt the sting of the grunge generation. They simply couldn't understand the anger. Just a year before he committed suicide in 1994, Nirvana's Kurt Cobain spoke at length in an interview in Seattle about his unstable home life as a child, when he was shuttled back and forth among relatives after his folks divorced when he was 9. He couldn't stand hippie idealism, he said, because he felt that the hippie generation— his parents—did such a poor job of raising kids. "Every night at one point, I'd go to bed bawling my head off," he told me. "I used to try to make my head explode by holding my breath, thinking if I blew up my head, they'd be sorry." Chris Cornell, who was then lead singer for Soundgarden, was amused around the same time when adults complained about his doom-laden songs. "The anger in rock 'n' roll is going to get worse," he said in 1994. "Just as the world was a harder place for my generation, it's even tougher for kids who are 10 and 12 today. It's so much of a jungle out there ... so much more negativity and violence and with no family support system for millions of those kids." That prediction came true in the music of such bands as Bakersfield's Korn, whose rap-metal sound struck most critics as simply an artless echo of such valued groups as Rage Against the Machine and Nine Inch Nails. But young rock fans responded to lead singer Jonathan Davis' vivid tales of childhood suffering, including molestation. Staind's Lewis also points to Korn's self-titled debut album in 1994 as a eye-opener for him. "I couldn't believe Jonathan had the strength to come out and say all the things he did about his own life," he said. "It helped me open up and let it fly." Lewis—who traces his gift for melody to the Cat Stevens, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and Gordon Lightfoot albums he heard around the house as a boy—doesn't like to speak in detail about his childhood. He says he had low self-esteem and often felt terribly alone, especially after his parents divorced when he was in his early teens. In "Fade," one of the band's most popular and darkest songs, he seems to be crying out at the abandonment he felt as a child: "You were never there for me." About his childhood, he only adds, "I've always been pretty insecure. That's my life's programming. In 'It's Been Awhile,' I'm basically talking about what my life was for the first 26 years... before things started getting better." Lewis attributes his improved outlook to his marriage three years ago and the increasing sense of self-worth that his music has brought him. "You know the only thing I've really taken into consideration when writing is to know at the end that I haven't said anything I shouldn't have," Lewis says near the end of the interview. "There are a lot of artists out there, from the way Britney Spears dresses to some of Eminem's talk about smacking [women] and beating up girls, that really don't think about the impact they are having on these young, moldable lives." For Lewis, the music's impact was driven home a few months ago when an Illinois teenager was so affected by Staind's "Outside" that he taught himself to play the song on the guitar, then recorded and listened to it before hanging himself. "Waste," a song on the new album, warns against the futility of suicide.

"I was crushed by that," he says. "Music has always been my therapy, a

positive force. Before I ever thought about writing songs, I started

writing poetry in junior high school and high school. I would fill

these five-subject notebooks and it helped me through some rough

periods. The only difference now is I was more surprised than anyone

when people started coming up to me and saying they understand just

what I was saying. I thought I was just telling my story." |

Main | News | Band | Music | Pictures | Videos | Articles | Tabs | Downloads | Stuff | TV | Tour | Links | Guestbook | Site Info